#mine: eretria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A “revisionist” article on the battle of Marathon and its historical significance, with some critical observations of mine on this text

The “revisionist” article to which I refer is written by Dutch historian Jona Lendering, who runs the well known website Livius. I reproduce below in its entirety Lendering’s article on the battle of Marathon and its historical significance (or rather, according to him, insignificance). After his text, I present my critical remarks on it.

“The Significance of Marathon

Battle of Marathon: famous clash between a Persian invasion force and an army of Athenians in 490 BCE. Its signicance is greatly exaggerated

It often said that the battle of Marathon was one of the few really decisive battles in history. The truth, however, is that we cannot establish this with certainty. Still, the fight had important consequences: it gave rise to the idea that East and West were opposites, an idea that has survived until the present day, in spite of the fact that “Marathon” has become the standard example to prove that historians can better refrain from such bold statements.

Presenting Marathon – Then and Now

The Spartans were the first to commemorate the battle of Marathon. Although they arrived too late for the fight, they visited the battlefield, inspected the dead, and praised the Athenians. The story is told by Herodotus, note the author of our main source for the fight. The very first question we ought to ask is why he chose to tell it. After all, his ambition was to record “great and marvelous deeds”, and the late arrival of the reinforcements was neither great nor marvelous. The Spartan presence at Marathon, however, served to present the battle that had been, or ought to have been, a fight by all Greeks.

That “Marathon” had been more than a normal battle, was hardly a new idea. Prior to Herodotus’ writing, monuments had already been erected, which presented the warriors as the equals of the heroes of the Trojan War. Other monuments, like the one mentioned by Pausanias, presented the dead as defenders of democracy: Pausanias mentions an Athenian “grave in the plain with are stones on it, carved with the names of the dead in their voting districts”.note A monument erected in Delphi presented the ten tribes and lauded the democratically elected Miltiades, but conspicuously ignored the polemarch Callimachus.

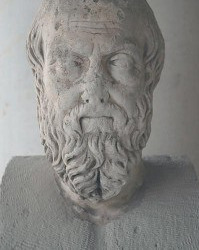

Herodotus of Halicarnassus

Framing the Battle

Herodotus chose not to present the battle in the same way. Knowing that the Persians had returned in 480 and had tried to conquer Greece, he interpreted the battle as a first attempt to do the same, which made the fight important for all of Greece. This is unlikely to be a correct judgment: the Persian army was too small for conquest and occupation, and most historians have rejected this.

What they did not reject, was the context in which Herodotus presented the violent actions. His Histories presuppose an elaborate model of action and reaction, which is Herodotus’ way to express historical causality: Cyrus conquered the Greek towns in Asia (action), they revolted (reaction), a war broke out in which Athens and Eretria supported the rebels (action), Persia restored order and decided to subdue the allies (reaction), the Persians came to Attica (action), where the Athenians defeated them at Marathon (reaction), so the Persians returned with a bigger army to avenge themselves.

This pattern of action and reaction is unlikely to correspond to historical fact. After all, the first action and the first reaction are separated by a considerable period, and the campaign of 490 was not aimed at the conquest of Greece. So, while Herodotus’ sequence of the events between 500 and 479 is probably correct, we may have some doubt about the causal connections. The Halicarnassian may in the end turn out to be right, but that is not now at issue: what needs to be stressed is that the framework in which we place the battle of Marathon, was created by Herodotus.

This framework also presents the struggle between the Greeks and the Asians as going back to times immemorial. The very first part of the Histories is a slightly ironic account of some ancient legends about women being carried away, but Herodotus continues by pointing at “the man who to the best of my knowledge was the first to commit wrong against the Greeks”, king Croesus of Lydia. The restriction “to the best of my knowledge” suggests that Herodotus believed that the conflict had started earlier. Herodotus is not just the father of history, he is also the father of the idea that East and West are eternal opposites.

Even more importantly, he is the first author to make this antagonism something more than a geographical opposition. The Asians were the slaves of the great king, and they went to war because the ruler ordered them to, while the Greeks were citizens of free cities, who obeyed the law and went to defend their liberty. This is borne out by the words of the Spartan exile Demaratus to Xerxes:

Over the Greeks is set Law as a master, whom they fear much more even than your people fear you”.note

This speech is, of course, one of Herodotus’ own compositions: not only are “tragic warners” in the Histories invariably speaking on behalf of the author, but the topic under discussion, the tension between the rule of a leader and the rule of the law, is typical for the political debate in democratic Athens.note

Herodotus’ framing of the Persian Wars as a struggle between a monarchical Asia and a free Greece explains his authorial choices. He might have mentioned the Spartan visit to the battlefield very briefly, but inserted a long digression, because the incident, although completely irrelevant for the battle, was useful to convert Marathon into a panhellenic event.

Nineteenth-Century Theories

Greece versus Asia: although popular in the classical age, this theme lost relevance in the Hellenistic age. Once Rome had seized power, the main opposition was that between the barbarians outside the Empire and the civilized Mediterranean city dwellers. When Christianity became popular, the main antagonism was between pagans and orthodox believers. In the Early Middle Ages, new self-identifications and oppositions arose: the scholars of Constantinople believed that Islam was the archenemy of the Byzantine Empire, whereas in the Carolingian Empire, scribes believed in an antagonism between Islam and those who were called “Europenses”. The first reference to Europeans as a cultural unity is the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754.

For centuries, the inhabitants of western Europe associated their culture with Rome and Christianity. In the eighteenth century, however, the famous German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann created the modern paradigm that Rome had merely continued Greek culture, and that Athens was the real origin of western civilization.

This new idea was successful, and in the early nineteenth century, the belief that Athens was the cradle of a freedom-loving, rational European civilization, was fully accepted. It was freedom, philosophers argued, that had at Marathon been defended by the Athenians. Because their victory had inspired other Greeks to resist Xerxes, Marathon had been an important battle: in Marathon, the foundations of western civilization had been laid. The British philosopher John Stuart Mill judged that “the battle of Marathon, even as an event in English history, is more important than the battle of Hastings”.

That bold, often repeated statement, is based on three assumptions. The first is that the Athenians were fighting for the independence of Greece. The pre-Herodotean monuments prove that this was not the perspective of the participants: Athenian democrats fighting against a Persian army that wanted to bring back the tyrant (sole ruler) Hippias. As indicated above, it was Herodotus who introduced the panhellenic element.

The second assumption is that the political independence of Greece guaranteed the freedom of its culture. In 1901, the great German historian Eduard Meyer wrote in his Geschichte des Altertums (“History of Antiquity”) that the consequences of a Persian victory in 490 or 480 would have been serious.

The end result would have been that some kind of religion … would have put Greek thought under a yoke, and any free spiritual life would have been bound in chains. The new Greek culture would, just like oriental culture, have been of a theocratic-religious nature.

The argument is, more or less, that the great king would have replaced democracy with tyranny, so that the free Athenian civilization would have vanished in a maelstrom of oriental despotism, irrationality, and cruelty. Without democracy, no Greek philosophy, no innovative Greek literature, no arts, no rationalism. In this sense, the Greek victory in the Persian Wars was decisive for Greek culture.

The third assumption is that there is continuity from ancient Greece to nineteenth-century Europe. This sociological statement has never been properly tested, even though there is an obvious counterargument: after the fall of Rome, people did not recognize this continuity. The “Europeans” were not recognized as a cultural unity until 754, and when they were, they were Frankish Christians fighting Iberian Muslims, not Greeks fighting Asians. Some scholars (e.g., Anthony Pagden) have tried to solve this problem by arguing that, in spite of the fact that nobody had noticed it, the spirit of freedom had always been there, just like the spirit of monarchism had always remained alive in the East, influencing individual behavior. This type of argument is called “ontological holism”, and is better known from Marx’ idea that history was forged by the struggle between classes, or the notorious idea that history was a war between races. Class struggle, race war, or the clash between free Europe and tyrannical Asia are abstractions that do not really exist.

A more sophisticated way to refute the counterargument is the idea, best known from Jacob Burckhardt’s famous Geschichte der Renaissance in Italien ("Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy", 1867), is that the Renaissance was a rebirth of Roman civilization and that Winckelmann was the first scholar who understood that Roman civilization had been a continuation of Athenian civilization. This cannot be discarded out of hand, because social scientists have never developed the tools to test such bold statements about continuity.

Meyer’s View Assessed

Today, the German scholar Max Weber is best known as the father of sociology, but he started his career as an ancient historian. In 1904/1905, he published the two “Critical Studies in the Logic of Cultural Sciences”, in which he investigated the epistemological foundations of the study of the past. The second essay deals with “Objective Possibility and Adequate Causation in Historical Explanation”, and has become rightly famous. As it happens, one of Weber’s examples is Meyer’s analysis of the meaning of Marathon, which is shown to be the result of a counterfactual argument: if the Persians had won, the preconditions would not have been met for the rise of Athenian civilization. But, Weber argued, this was nothing but speculation. Counterfactual arguments are usually fallacious.

For example, how did Meyer know that the Persians, after a victory in the Persian Wars, would have put an end to democracy? We must pause for thought when we read that Herodotus explicitly states that the Persian commander Mardonius supported Greek democracy.note Another point is that very few historians, right now, will accept that the ancient Near East was “of a theocratic-religious nature”: it was in Persian Babylonia that astronomers developed the scientific method. Plato and Aristotle might have lived in a Persian Athens. Likewise, Eric Dodds’ The Greeks and the Irrational (1951) meant the end of the idea that Greek culture represented a more rational view of life.

So, Meyer’s reading of the Persian War has been decisively challenged. We cannot make bold statements about the meaning of Marathon. Unfortunately, not everybody is aware that there are limits to what we can understand about the past: over the past years, several books have appeared that pretend that there is a direct continuity from Marathon to our own age. Historians and social scientists have something really important to discuss.

[Originally published in the Marathon Special of Ancient Warfare (2011).]

This page was created in 2011; last modified on 15 October 2020.”

Source: https://www.livius.org/articles/battle/marathon-490-bce/the-significance-of-marathon/

Jona Lendering is Dutch historian and runs the website Livius (see about him https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jona_Lendering )

And now my critical remarks on Lendering’s article:

1/ In the battle of Marathon Athens, a free city-state and fledgling ancient democracy, dared to resist the most powerful Empire the world had seen till that time and, against all odds, she won the day. If one bears this truth in mind, the historical significance of the battle of Marathon is obvious for all humans of all ages who see with favor the cause of freedom and sympathize with peoples who dare to fight powerful empires in order to defend their independence. This is even more the case for people who see with sympathy democracy and the defense of democracies face to imperialism and authoritarianism.

2/ The fact that, when the Athenians fought at Marathon, they had quite naturally first of all in their minds the defense of their city does not exclude the Panhellenic significance of the battle. Marathon was not of course the decisive and final battle of the Persian Wars. However, it was the battle which proved to the Greeks that the Persian Empire was not invincible. Moreover, as Herodotus says, the Persians had already decided to subjugate (in the one or the other form) the whole mainland Greece. If they had won at Marathon and taken Athens, the Athenian army and above all the powerful navy that Athens built in the years 490-480 BCE would have been out of the equation. If one properly understands the critical role played by Athens in the Greek defense during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 480-479 BCE, it becomes evident why Marathon, although not the decisive battle itself, played a major role in the eventual outcome of the Persian Wars.

3/ It is true that, as Herodotus writes, the Persians and more particularly Mardonius experimented with democracy in the Greek cities of Asia Minor which they occupied again after the quelling of the Ionian revolt. We can only speculate about the reasons which made a Persian satrap (moreover, according to Herodotus, the most hawkish one) introduce democracy in the occupied by the Persians Greek cities. However, we should not have illusions about what “democracy” meant in such conditions: this “democracy” was no more than a form of limited self-government of cities which were in fact under the total domination of the Persians. I don’t think that we can compare this “democracy” under Persian control with the great democratic experiment of sovereign Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE and with the tremendous stimulus the latter gave to Greek political thought and intellectual life.

Moreover, one of the aims of the Persian campaign in Attica in 490 BCE was to reestablish as tyrant of Athens the Peisistratid Hippias, who had been expelled about two decades before, a thing which means that there would be no repetition in Athens of Mardonius’ experimentations in Ionia. The other aim of the Persian campaign was of course to punish the Athenians for their previous support to the Ionian revolt. This punishment would have meant destructions of the one or the other extent in Athens, but also captivity and deportation to Persia of an important part of the Athenian population, as the Persians were already doing with Eretria, the other Greek city besides Athens which had sent troops to support the revolted Greeks of Asia Minor. Families and groups which had been the most hostile toward the Peisistratids and had played a prominent role in the political life of the city and in its involvment in the Ionian revolt would have been of course the first among the deported (if the Persians and Hippias did not choose to put them to the sword). Now, I think that it is obvious that an Athens largely depopulated and under a vindicative pro-Persian tyranny could not have become the intellectual and artistic center of Greece that she became after the Greek victory in the Persian Wars. So, although Lendering is right that the Persians would not have imposed some kind of “oriental mystical religion” on Athens, I think that it is evident that, if the Athenians had lost at Marathon and the Persians had subdued Athens, a very important damage in the development of the classical Greek civilization would have occured.

4/ Herodotus is not the inventor of some eternal opposition between West and East and between Europe and Asia. The “West” and “Europe” as civilization and as political and cultural identity meant nothing for him; it is for instance obvious that he saw as far more relevant for the ancient Greek cultural identity the Egyptians than the Celts. Herodotus chose for sure as the central theme of his work the conflict between on the one hand Greece and on the other hand the Persian imperial monarchy, which had under its command all the resources not only of Iran, but also of the ancient civilizations of the Near East and of parts of Central Asia and of India. But this conflict, which culminated with Xerxes’ invasion of Greece, was of course a historical reality, not some invention of Herodotus.

Now, concerning the ideological aspect of the same conflict as opposition between on the one hand freedom and law and on the other hand despotism, again what Herodotus writes is not out of touch with reality, because, put aside some rhetorical exaggerations from Greek writers (less in Herodotus and more in later authors), there was a very real ideological dimension in the Persian Wars. I say this because the Persian Wars were the endeavour of the Persian imperial monarchy, characterized by an immense concentration of power in the hands of the Great King, to subdue the Greek free city-states, which were implementing to various degrees and in various forms institutional experiments with rule of law, balance of power, political participation of the people, and active citizenship, and even, in the case of Athens, an institutional experiment with political equality between free people, equal free speech, and direct political democracy. I don’t say that we should idealize these experiments, first of all because slavery was a feature (and a major flaw) of the ancient Greek social and economic life (although this was also the case with most societies of the ancient world, including of course the Persian Empire), secondly because among these city-states there were Sparta and some other Dorian polities ressembling Sparta, which were undoubtedly militaristic and one-sided in their development. However, despite these flaws and historical limitations, in their pluralism the institutional experiments of the ancient Greek republics and first of all of course Athens were the great precusors of later historical developments and experiences with political, social, and individual freedom and with democracy. Therefore, the successful defense of these republican Greek experiments face to the autocracy and imperialism of the Persian Empire is obviously of major importance not only for the political and military history, but also for the history of ideas.

All this does not mean that we should subscribe to some essentialist opposition between a supposedly by nature free-loving West and a supposedly by nature despotic/servile East, notions that Lendering correctly criticizes. And I remind here that Herodotus is far more nuanced in his presentation of Greeks and non-Greeks than many believe: on the one hand, he describes tyranny and tyrants like Periander, Polycrates, and Gelon as an important problem of the Greek world, and most scholars believe today that his work contains implicit warnings about the Athenian imperialism of the Periclean and post-Periclean age; on the other hand, he accepts that the “Oriental’ monarchs, although for sure too powerful for the Greek standards, were not necessarily hybristic despots (Cyrus the Great was seen as “father” by the Persians, Egypt before Cheops was governed according to justice and custom), and he describes freedom-loving “barbarians”, like the Scythians, the Massagetae, and even the Persians, when they followed Cyrus and overthrew the yoke of Astyages and of the Medes. Moreover, in the “Constitutional Debate” of Book III of Histories Herodotus presents the Persians as able to envision other constitutional dispensations than monarchy, including even democracy.

5/ Marx’ theory of history is not of course above criticism, but I believe that Lendering’s grouping in his text above of Marxism with the racialist (racist) theories on history as instances of “ontological holism” is very unfortunate on many levels.

6/ Lendering alludes in his text to some idiosyncratic and erroneous views of his on the origin of science and scientific method, for instance to his belief that the scientific method developed in Antiquity not in Greece, but exclusively in Babylonia, and that Aristotle would have borrowed his theory of science, of scientific syllogism, and of scientific truth from the Babylonian “Astronomical Diaries” (see with more details about his views on these topics and my criticism of them https://at.tumblr.com/aboutanancientenquiry/the-babylonian-astronomical-diaries-and-their/9kwxss8gyvuf and https://at.tumblr.com/aboutanancientenquiry/the-babylonian-astronomical-diaries-and-their/8m68it6lzmru ). Moreover, contrary to what Lendering thinks, the reality that the ancient Greek civilization was not only rationalism had been understood before Dodds, as for example already in the 19th century Nietzsche had discerned the existence of the “Dionysian’ element in it. More generally, it would be illusory to search for some purely rationalist ancient civilization (and we should not forget that our own civilization has its own types of irrationality), and in fact one of the great triumphs of the ancient Greek culture was that it transformed the “irrational” in human life (extreme passions, reversals of fortune, undeserved suffering etc) and ‘irrational” myth into great literature, which contains immortal insights into the human condition. However, it is beyond doubt that rationalism too was something of major importance in the ancient Greek civilization. And I think that Lendering underestimates grossly the great innovations, breakthroughs, and contributions of the Greek rationalist thought and their importance for the intellectual and cultural evolution of humanity.

8/ I think that it is also beyond doubt that, although it is true that there is not some direct continuity between ancient Greece and Western Europe, the ancient Greek heritage played a very important role in the formation of the Western European cultural identity, either indirectly (via Rome and Western Fathers of the Church heavily influenced by Platonism like Augustine) or directly (above all with the rediscovery of ancient Greece in the last centuries of Middle Ages and in Renaissance). However, it seems that Lendering suggests that the Western European heritage is in fact exclusively Roman and Germanic and that ancient Greece has been included in this heritage rather artificially much later, a view which is shared today also by others in Western Europe. I don’t agree of course with this point of view, but I recognize that people have every right to include and exclude things from what they see as their cultural heritage and identity. Moreover, I recognize also that, although erroneous, such a point of view has at least the merit that it may facilitate the appreciation of the great ancient Greek civilization for what it was in itself and not just as an ancestor of the modern West.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

⁉️ + Ethan and Dorian

send a ⁉️ + a muse , & i’ll tell you what muse of mine i see interacting with yours !

Ethan

Jade Emily Radcliff Eretria Genevieve Talon Anabelle Moira Persephone

Dorian

Jade Emilia Regina Moira Haruko Persephone

0 notes

Photo

Eretria’s Princess Jasmine hairstyle appreciation post

#shannaraedit#the shannara chronicles#eretria#eretriaedit#ivana baquero#my stuff#mine: shannara#mine: eretria#its so grainy ugh#but she looked so good

751 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#shannaraedit#eretriaedit#the shannara chronicles#eretria#ivana baquero#mine#mine: the shannara chronicles

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivana Baquero, as Eva Villanueva in the season 2 of Alta Mar (High Seas) on Netflix.

#ivana baquero#alta mar#high seas#eva villanueva#The Shannara Chronicles#eretria#netflix#pan's labyrinth#alta mar s2#high seas s2#spanish actress#mine: gifs

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Something like that?” | TSC Rewatch » 1.06 - Pykon

#princess rover#tscgif#tscedit#amberle elessedil#eretria#the shannara chronicles#these dumbasses#2017#my stuff#my gifs#mine: new#mine: gifs#mine: the shannara chronicles#mine: princess rover#mine: eretria#mine: amberle elessdil#i hate them#shannara: pykon#mine: gif

691 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crackship request from Anon

Ivana Baquero and TWD Cast

#Ivana Baquero#Eretria#the shannara chronicles#Chandler Riggs#Carl Grimes#Twd#The walking dead#Crackship#Crossover#Au#Base gifs not mine#credit where credits due#credit to original owner#credit where credit is due

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eretria Rewatch

If you’re gonna keep insulting me, I should at least know your name. Eretria.

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

bitch me too the fuck

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I feel this connection to her that I can’t explain.

#shannaraedit#princess rover#princessroveredit#amberle x eretria#the shannara chronicles#shannara spoilers#otp: you came back#WISH i could ship lyretria as much as them#but i cant I CANT#LIKE#i like them#and i love that eretria has someone who loves her now#BUT#i need to see the buildup???#theyre already together???#i need to see it happen to get invested I NEED TO BE THERE FOR THE JOURNEY#*#mine: gif#mine: the shannara chronicles

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

the only acceptable conclusion to a f/f/m love triangle is for the two girls to forget about the guy and date eachother

#wlw#love triangle#girl meets world#rucaya#rilaya#the shannara chronicles#wil x amberle#wil x eretria#princess rover#riverdale#lucaya#barchie#varchie#beronica#text#mine#lgbt#lesbian#bisexual#wlw ships#wlw culture#500#1k

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shannara Chronicles lockscreens (more lockscreens here)

#eretria#amberle#the shannara chronicles#shannaraedit#the shannara chronicles amberle#amberle elessedil#wil ohmsford#the shanara chronicles eretria#the shannara chronicles wil#lockscreens#shannara chronicles lockscreens#mine

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“You’re still here.”

“I wouldn’t leave without a proper goodbye.”

935 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#the shannara chronicles#shannaraedit#eretriaedit#ivana baquero#eretria#mine#mine: the shannara chronicles

154 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivana Baquero, as Eva Villanueva in the Alta Mar season 3 trailer.

#Ivana Baquero#alta mar#alta mar s3#alta mar season 3#netflix#netflix series#The Shannara Chronicles#eva villanueva#eretria#spanish actress#high seas#high seas season 3#mine: gifs

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bisexual Badasses 4 bisexual female characters you don’t want to be on the wrong side of. Sara Lance - Legends of Tomorrow Eretria - The Shannara Chronicles Cara Mason - Legend of the Seeker Anne Bonny - Black Sails

#sara lance#eretria (shannara)#cara mason#anne bonny#black sails#bs anne bonny#legend of the seeker#legends of tomorrow#the shannara chronicles#bisexual#bisexual female characters#bisexual badasses#my graphics#mine

103 notes

·

View notes